Ocean of trauma

Vegan Society of Canada News

Published November 3rd 2020

Updated August 31st 2023

While human animal exploitation in slaughterhouses is horrendous, the suffering and abuse of workers in the global fisheries industry surpasses it.

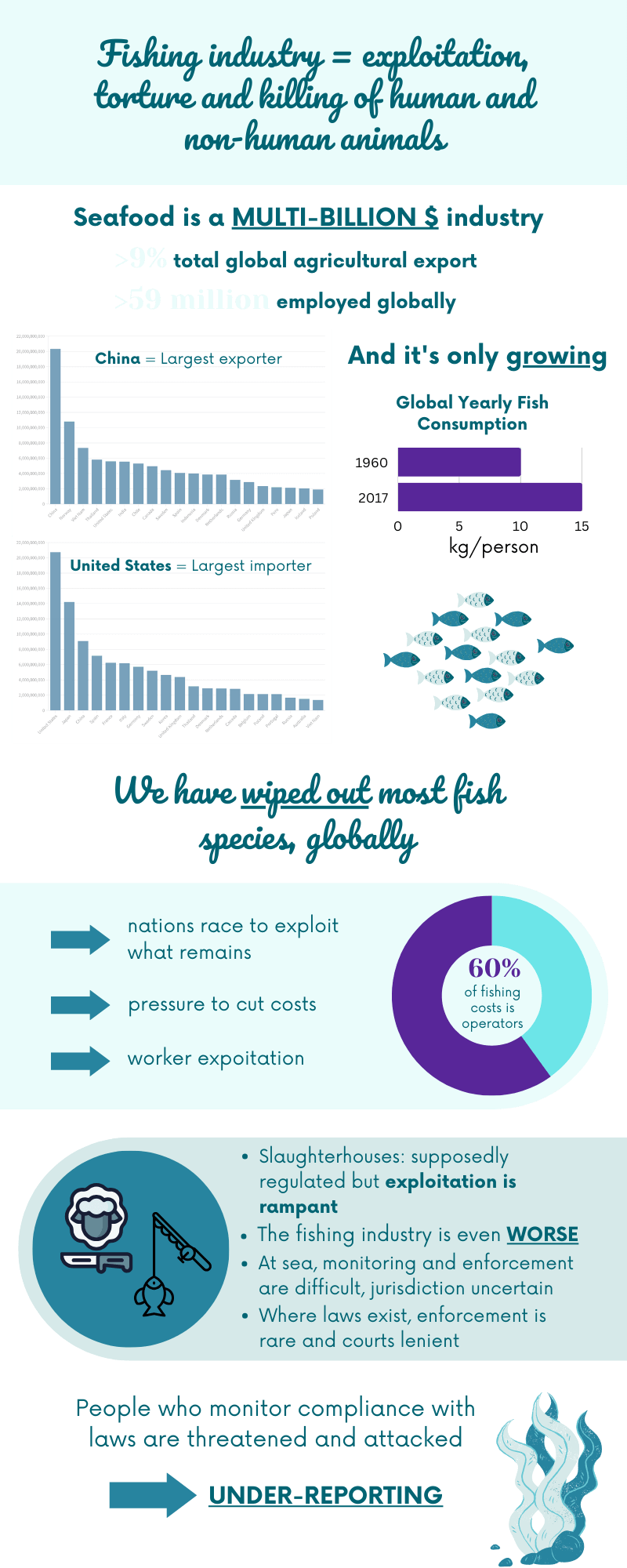

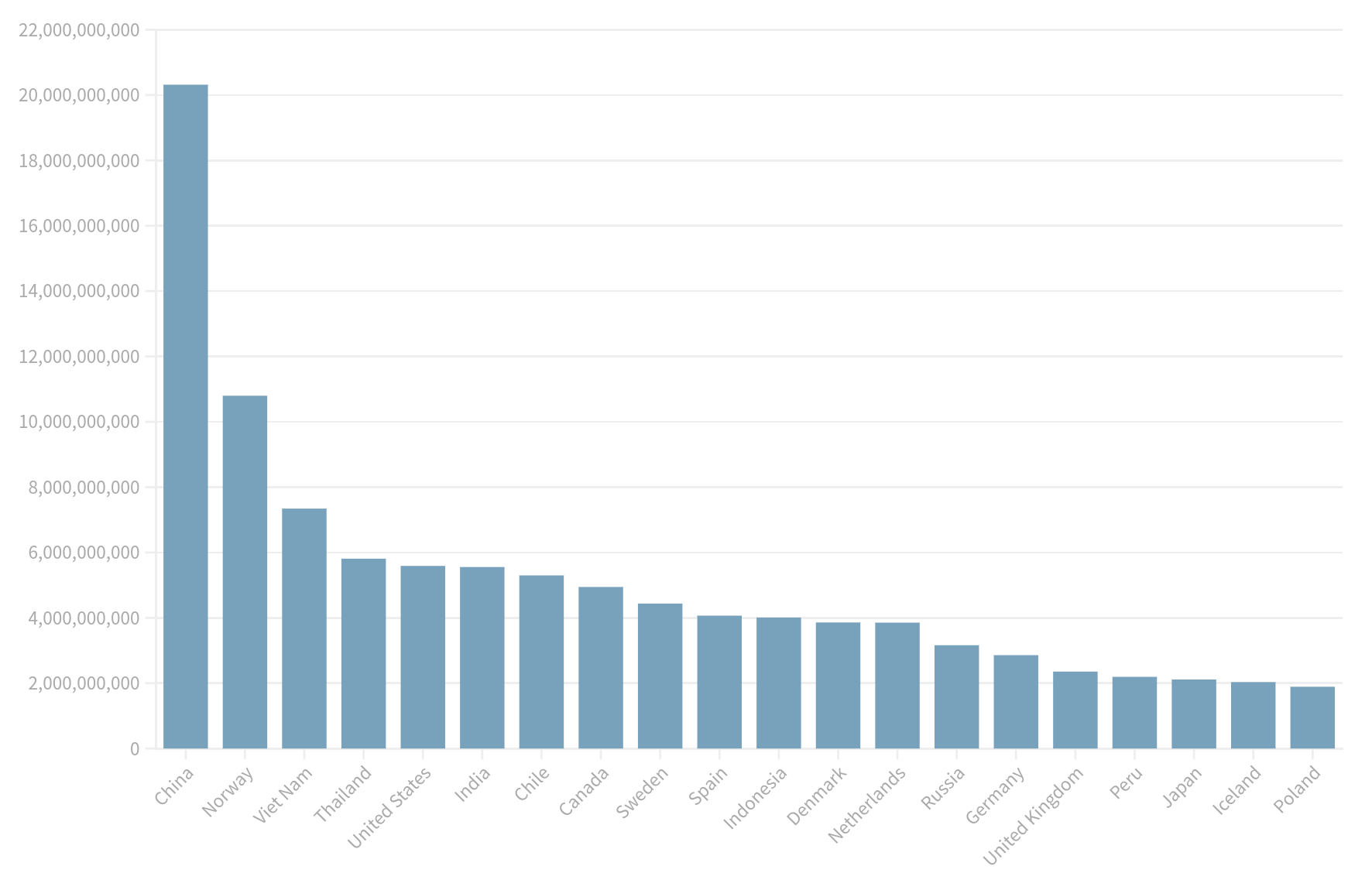

Seafood is a multi-billion dollar industry; it represents more than 9% of the total agricultural export and employs over 59 million people globally. As the graph shows below, many countries import some seafood, with China being by far the largest exporter.

It is easy to see that the bulk of sea animal exports come from countries with rampant abuse of animal rights, whether human animals or not. As with most everything else we consume, we tend to import misery from other countries, choosing to ignore various abuses when production is hidden from consumption.

Figure 1: Value of aquaculture export by country in USD (2016)

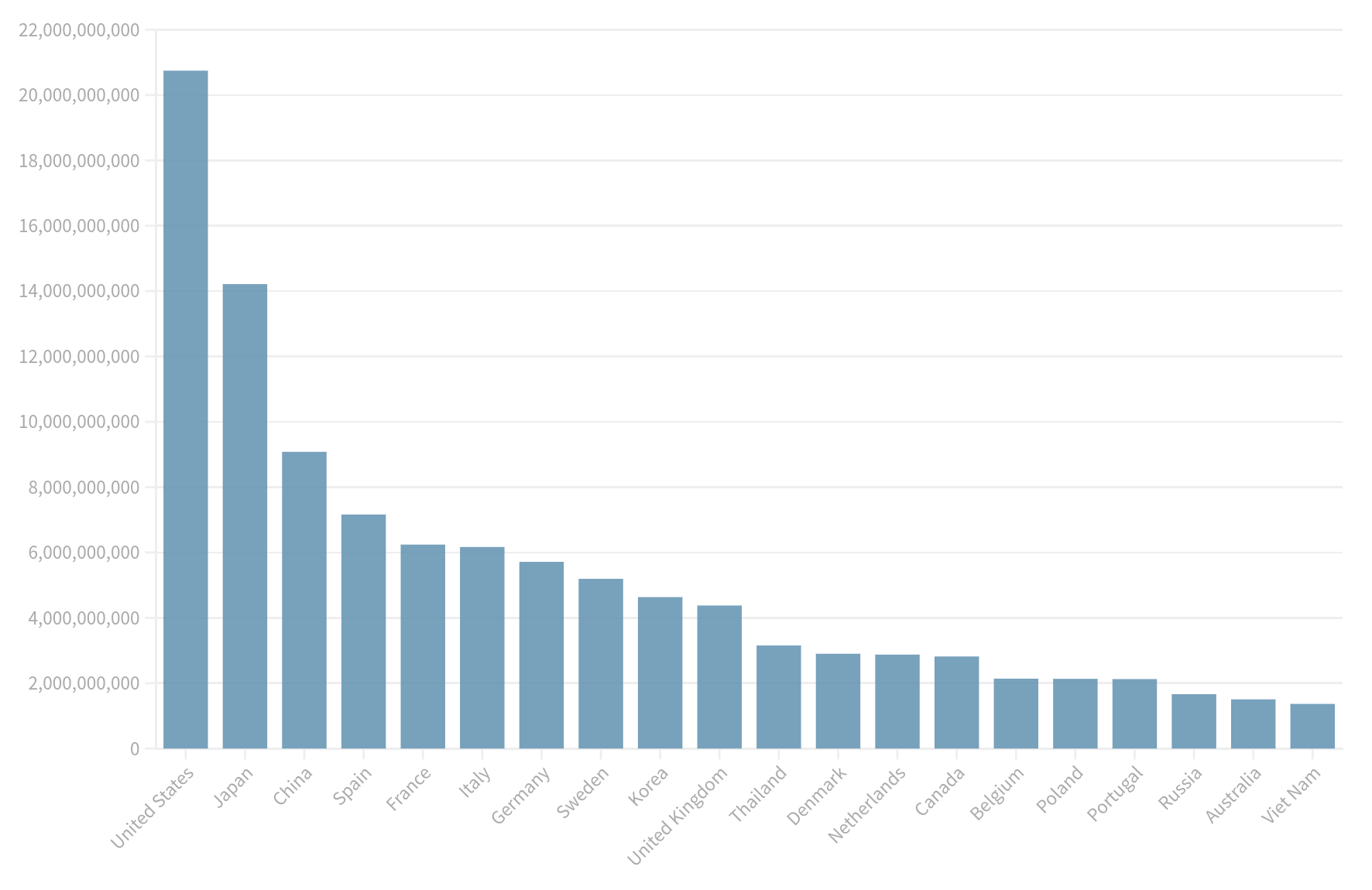

Figure 2: Value of aquaculture import by country in USD (2016)

The problem is fish consumption continues to increase year after year, from about 9.9 kg per person in 1960 to 20.5 kg in 2017. As various organizations, like Lancet’s planetary diet, make fish their protein of choice, consumption keeps increasing. Our exploitation of animals has almost wiped out most fish species globally. This race to the bottom to exploit what remains is putting pressure on corporations to cut costs, and since the cost of labour can be up to 60% for fishing operators, this results in an attempt to drive down the cost of labour by the exploitation of workers, even including torture and killing.

In countries which are supposed to have acceptable laws protecting workers, their exploitation is rampant in slaughterhouses. Now imagine floating slaughterhouses in international waters where legal implementation is murky at best, and where the killing is hidden by miles and miles of water. This is the current problem with the seafood industry.

The standards of the Vegan World Alliance and our certification are one of the most stringent in the world. Every day, we’re in the fight to end exploitation of all animals, and we will not tolerate rolling back the progress that has been made to end the exploitation of human animals.

To that end, our standards contain various requirements with regards to the conditions of human animals. Most regrettably, many products that are “certified” vegan today are made in countries with rampant child labour, forced labour, slavery and practices similar to slavery like debt bondage and serfdom, where inspections done without interference is nearly impossible. This exploitation of animals will not bring about our vision, and you have our commitment that we will never certify vegan such products.

Before we continue let’s quickly review some terms we use in our standards with regards to the exploitation of animals:

Forced Labour (International Labour Organization's Forced Labour Convention 1930 #29)

All work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.

Slavery (League of Nations 1926)

Status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised.

Debt Bondage (UN Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery 1956)

The status or condition arising from a pledge by a debtor of his personal services or of those of a person under his control as security for a debt, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied towards the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined.

Serfdom (UN Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery 1956)

The condition or status of a tenant who is by law, custom or agreement bound to live and labour on land belonging to another person and to render some determinate service to such other person, whether for reward or not, and is not free to change his status.

Trafficking in Persons (Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime 2000)

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) have been used.

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered "trafficking in persons" even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article.

Child shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.

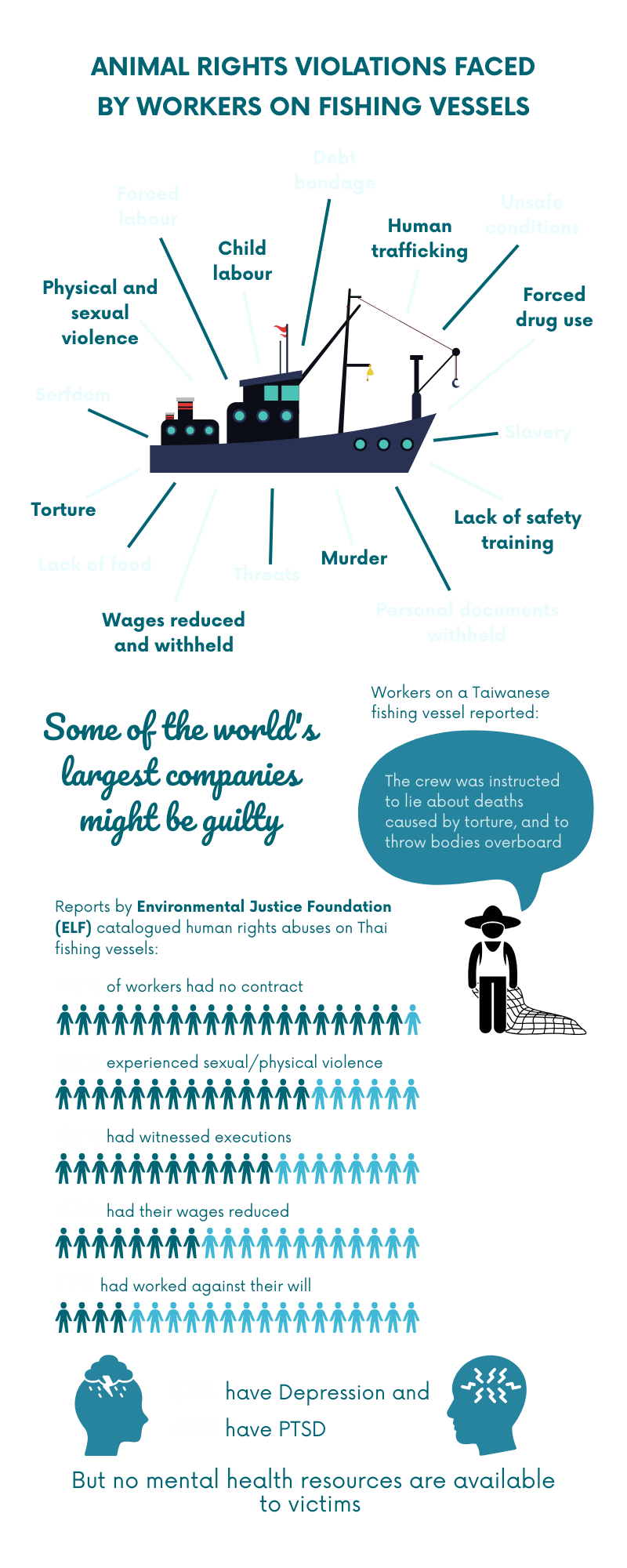

Many think those practices don’t exist, but unfortunately they do and sometimes they are perpetrated by some of the largest corporations in the world. In 2018-2019, an investigation found a fishing vessel operating in the Indian Ocean under a Taiwaneese flag with outrageous working conditions for those onboard. Some of the workers described physical abuse, including beatings:

He took a sandal and hit me on the back of my neck but I was silent and kept working. He hit me five times, he was a big man and it was painful. I knew that if I fought back I would go to jail.

I remembered my family and thought who would feed them if I went to jail?

They also found an instance of a crew member being locked in a freezer that could easily be considered torture:

I threw bait fish at the door and kicked the door all over in an attempt to get them to unlock the door. The door was still locked for what felt like 15 minutes. I felt very stiff and found it difficult to breathe. Finally the door was opened and I heard the captain say to the rest of the crew: ‘If he dies just say that he died in an accident and then we will throw his body into the sea’.

The same crew member was also electrocuted:

This tool is used to electrocute fish to death so you can imagine what it does to humans. After he took the metal away from me I felt weak and was shaking on the floor.

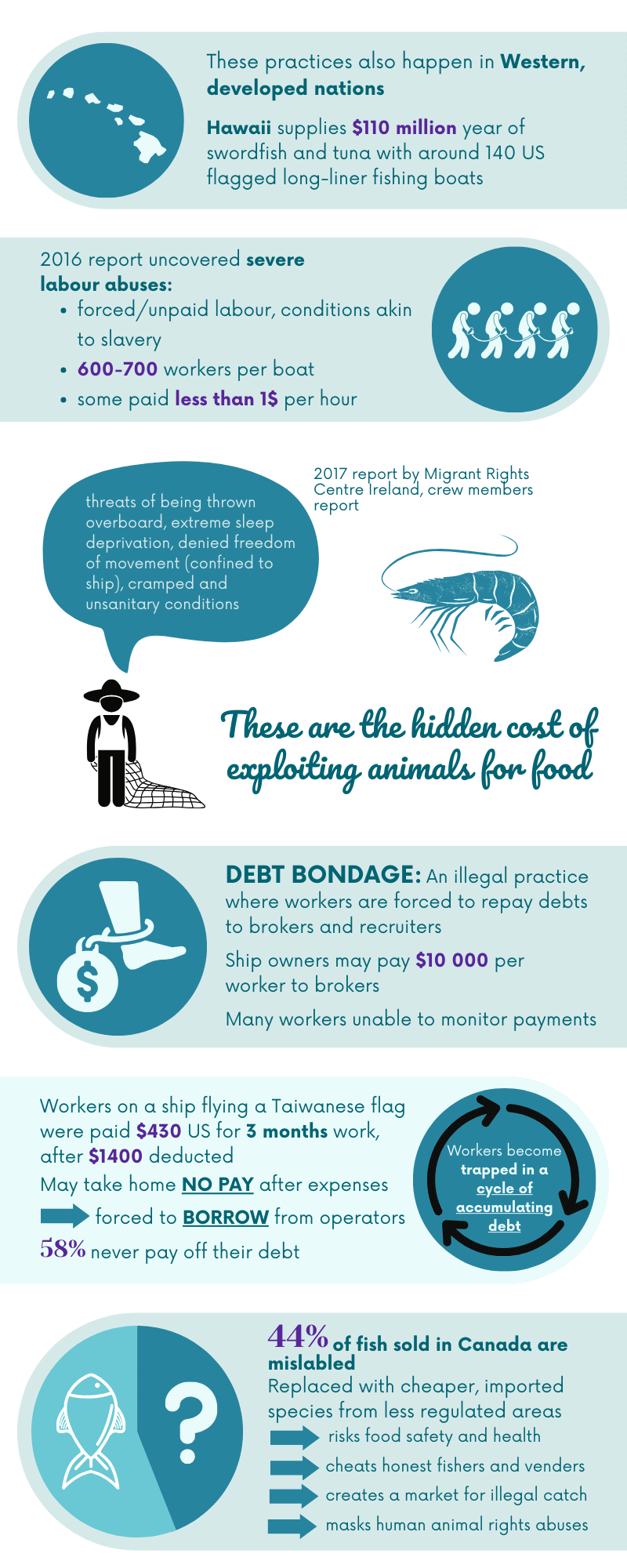

This crew member became partially deaf as a result of this incident. For all this, the crew member was paid $430 USD for three months, with a total of $1,400 USD deducted from his salary. He was afraid for his life and he feared he would be murdered if he fought back.

Murder? You may be thinking that’s an exaggeration, but that is exactly what happened in 2015 on the Taiwaneese ship Fu Tsz Chiun; Supriyanto was found dead with evidence of abuse. While the death of Supriyanto was not ruled a murder, murder is much too nice a word to describe what happened in this case. We will not be sharing the harrowing photographic evidence of his death. His story and those of others in Taiwan are widely available on the internet, in the report from Greenpeace titled Misery at Sea, and this article from the Taiwaineese media titled Welcome to Taiwan: Beatings, Bodies Dumped at Sea and a Culture of Maritime Abuse.

Now let’s have a look at two of the major exporters where it’s theoretically possible to have the freedom of doing investigations without fear of reprisal: Vietnam and Thailand.

In a 2019 report titled Caught in the Net: Illegal Fishing and Child Labour in Vietnam’s Fishing Fleet, the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) catalogued various animal rights abuse on adults and children, including child labour. In their survey, 17% of vessels had at least one child working onboard with the youngest child being eleven years old, which is also illegal in Vietnam.

Furthermore, it was found that most of the children who are working do not attend school and are illiterate. The problem is laws are not being enforced, they are there to comfort other countries so they can point to various laws on the books, but nobody is implementing them. In the report the captain of a ship stated:

Laws are only there in theory. Implementation doesn’t happen. We can’t do anything about it, we have no power.

Further inspections of many vessels also showed that crews were fed low-quality, expired or rotting food. In addition, none of the crew interviewed in the report had a regular, agreed upon salary, which means they could end up coming back from a trip with no money after expense deductions, resulting in them having to borrow from the fishing operators to feed their families in the hope of repaying them on future trips. However, when asked if they were successful in repaying their debts on subsequent fishing trips, 58% of interviewees claimed they were not able to do so.

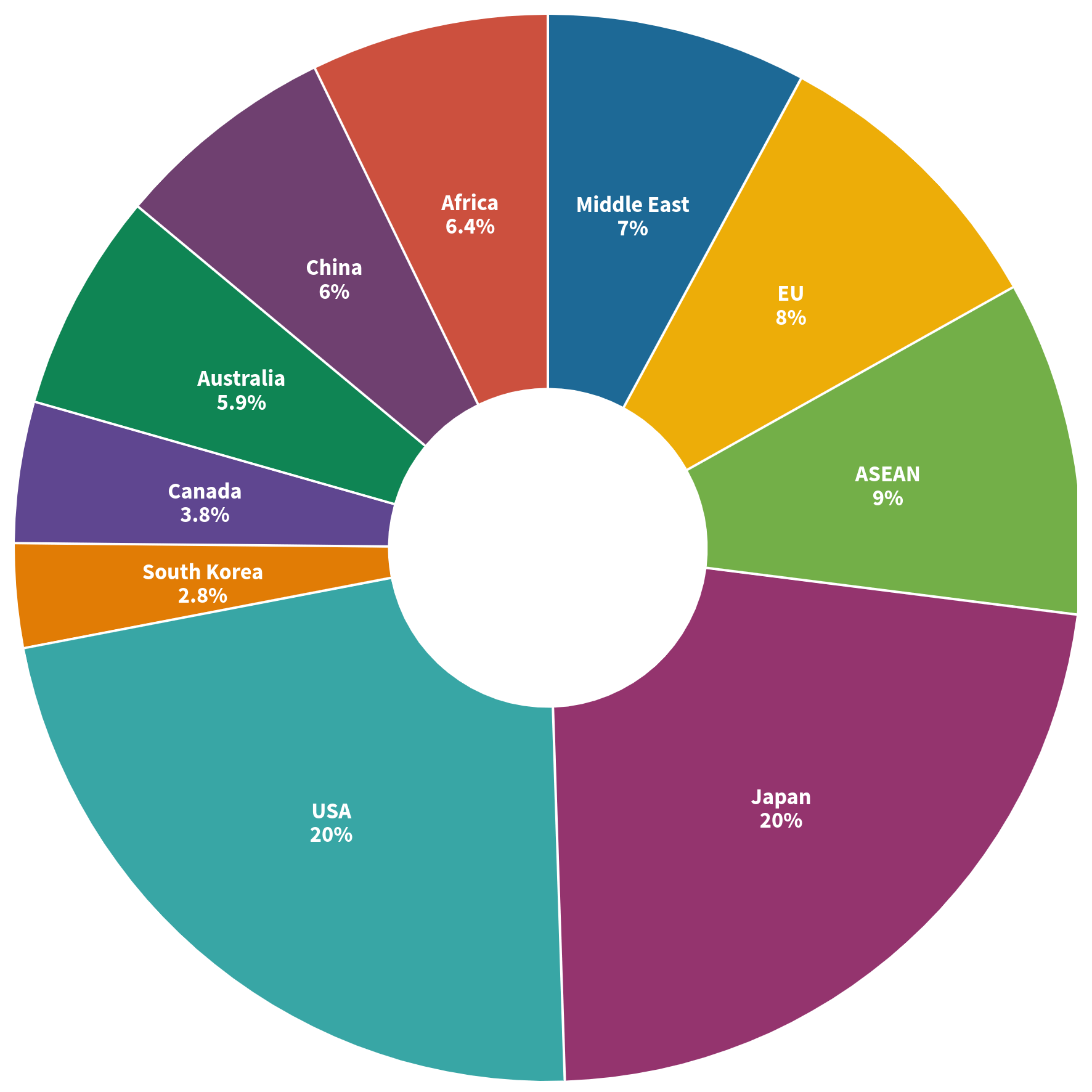

Thailand, on the other hand, is important as it is one of only two major markets for tuna processing, and the Pacific islands surrounding Thailand is responsible for 40% of the global tuna market. A 2015 report by the EJF titled Thailand’s Seafood Slaves documents the atrocities of the fishing industry. Thailand’s export seafood industry, worth 6.95 billions USD in 2018, is consistent with the global picture.

Figure 3: Share of Thailand 6.95 billion USD seafood export (2018)

Many serious issues were identified during interviews with crew members:

- 94% had no contract

- 80% reported never feeling free

- 68% reported sexual/physical violence

- 59% witnessed executions at sea

- 52% witnessed their boss/trafficker harming someone

- 47% reported at least one injury

- 44% reported lack of food

- 42% experienced wage reductions

- 23% were locked in a room during trafficking situations

- 17% worked against their will

- 17% were threatened with violence

- 11% attempted escape

- 10% were severely beaten

- 5.8% reported being forced to use drugs, for example methamphetamine, to make them work harder and longer

They describe horrendous treatment of workers:

Many brokers use intimidation, threats, violence and even torture and murder to keep men on fishing boats and make an example of those who resist or attempt to escape.

The various stories of trafficking and exploitation in the report are shocking and make for difficult reading. This is but one excerpt of one story of the life of Aung Kyi and his trafficker nicknamed Saw:

As the Ouway Meng boat returned to shore after 12 days at sea, Saw’s husband was waiting for him at the pier. Saw’s husband was accompanied by an Ouway Meng security guard and two other men, both armed with handguns. Aung Kyi was warned by Saw’s husband that these two companions were policemen. Saw’s husband handcuffed Aung Kyi at the pier and escorted him back to Saw’s compound, where he had Aung Kyi kneel on the floor. Placing the gun to Aung Kyi’s forehead, Saw’s husband demanded to know whether he ‘wanted to work or wanted to die’.

For those who can escape this torture and return home, the difficulties do not end there. There are no social programs to help them recover, and a survey showed 62% of these people had depression, and 46% had post-traumatic stress disorder. Even if by chance workers are not enslaved in some form, the life aboard Thai vessels is no pleasure. A 2013 survey reported that 25% of workers claim to work more than 17 hours per day.

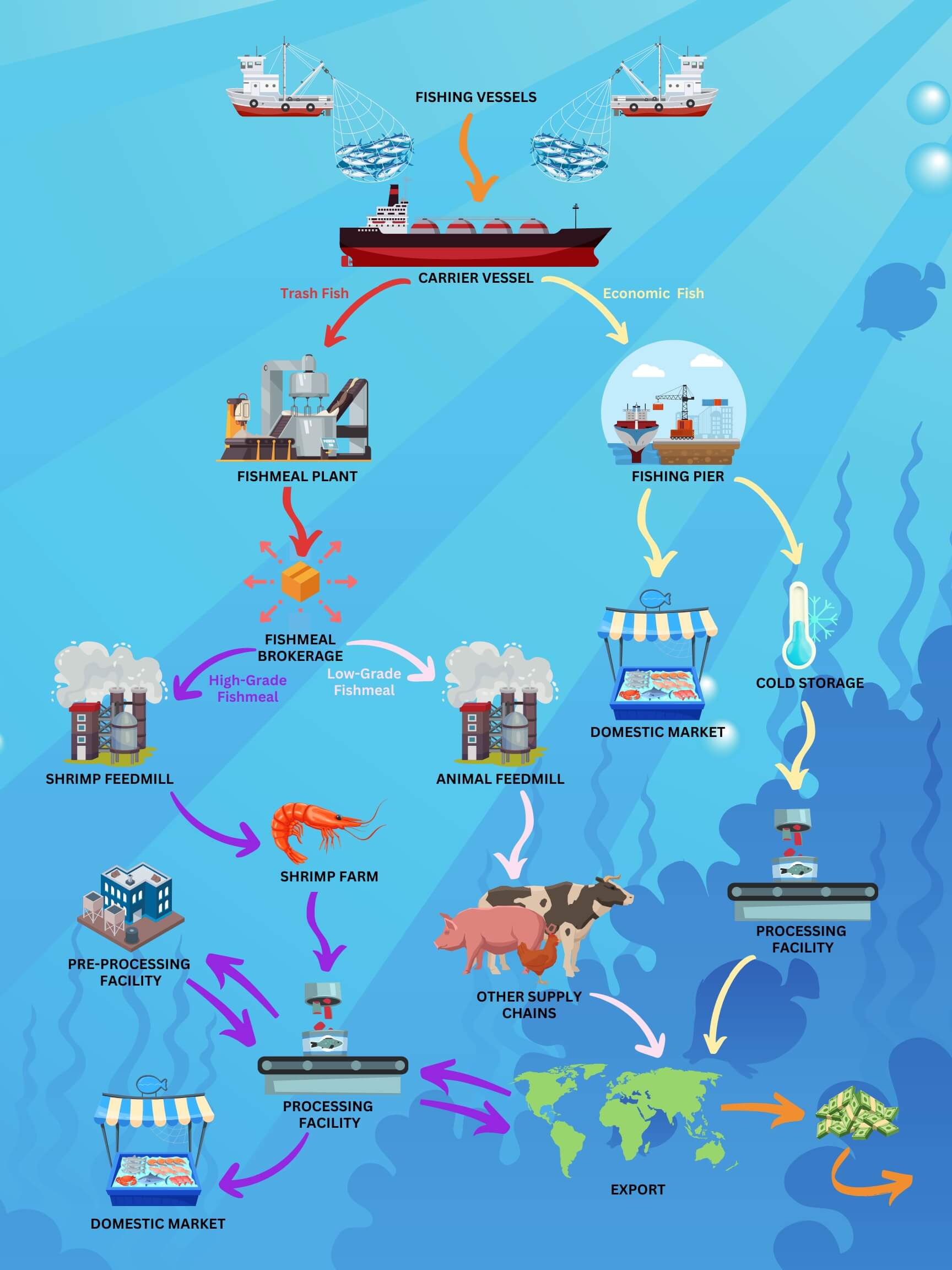

Furthermore, this is not only limited to fish for human consumption, but the supply chain of exploitation is deeply intertwined; some of the fish that do not make the cut for human consumption are used as fish meals for animal agriculture, shrimp farm, and as part of food sold in pet stores globally.

Thailand's supply chain

By various accounts, Thailand made good progress in addressing some of those issues. However, many problems still remain. A 2018 survey of 434 workers found:

- 34% reported being paid less than minimum wage

- 24% saw some form of pay withheld, sometimes for 12 months or more

- 34% reported not having access to their identity documents

This is only a small portion of the hidden costs of the animals we kill for various reasons.

You may think this happens in China and Thailand, but not in my country. But, let’s have a look at what investigations uncovered in the U.K. and Ireland. In a 2016 investigation, The Guardian reported:

A year-long investigation into the Irish prawn and whitefish sector has uncovered undocumented Ghanaian, Filipino, Egyptian and Indian fishermen manning boats in ports from Cork to Galway. They have described a catalogue of abuses, including being confined to vessels unless given permission by their skippers to go on land, and being paid less than half the Irish minimum wage that would apply if they were legally employed. They have also spoken of extreme sleep deprivation, having to work for days or nights on end with only a few hours’ sleep, and with no proper rest days.

Furthermore a majority of the high value prawn and fish catch of the Irish waters is exported across Europe, the Americas and the Far East. Their investigations have found a long list of animal exploitation including:

- Withholding of pay, arbitrary cuts to rates of pay agreed in recruitment contracts, forced unpaid labour on net and boat repairs in port.

- Rates of pay a fraction of the legal minimum and a fraction of what local or EU fellow workers are paid.

- Worker passports being withheld by owners/skippers.

- Workers denied freedom of movement, told to hide when inspectors or the Navy board, and being required to live onboard because of their immigration status.

- Severe sleep deprivation, with workers being required to work in near continuous shifts for several days without mandatory rest periods.

- Reports of verbal abuse and in occasional cases physical abuse such as slapping.

- Exposure to dangerous working practices.

- Workers fishing without mandatory Irish safety training certificates.

- Workers being left hungry, with insufficient money for food and no access to shops.

- Workers living in cramped conditions on vessels, in some cases without proper sanitary arrangements.

Those conditions amount to slavery or practices like slavery, but regrettably even when those things end up in court The Guardian found that they acted most leniently. For example, in a 2015 case, a judge dismissed the following case:

A judge dismissed the case of a prawn trawler owner who pleaded guilty to taking an Egyptian migrant crew member fishing when he had no safety training, deciding not to convict him because he was providing employment and had a clean record. Instead, he ordered him to pay €1,000 to a local charity.

Have things changed since 2015? As usual the simple answer is no, or not enough. A 2017 report by the Migrants Rights Centre Ireland titled Left High and Dry reported many deeply concerning practices:

The owner complained that he wasn’t fast enough and threatened him. ‘If you don’t work faster I will throw you overboard.’ The owner told him, ‘You are illegal in this country and will be sent back home.’ Money was paid into his bank account in his home country. He didn’t receive payslips and didn’t know how much he was receiving. He stated that, ‘The debt is a big problem for me. It keeps increasing.’ He is very stressed about the debt. ‘If I walk away from the boat, the little money I get, I won’t have any more, to pay little amounts off this loan.’ He describes how ‘sometimes I can’t take care of myself. I am so tired’.

They conclude by saying:

This research shows that there are still alarming levels of severe exploitation and non-compliance in this segment of the Irish fishing [industry].

We may be inclined to think that this problem is confined to Asia and some parts of Europe, and that all of this is an exception not the norm. Most unfortunately, we would likely be wrong.

The report looks at cases of exploitation in the U.S., most particularly around Hawaii which supplies swordfish and tuna to North America to the tune of $110 million per year with about 140 U.S. flagged longliner fishing boats. Their investigation uncovered the following:

Serious labour abuses including forced, unpaid labour, and living conditions akin to slavery were discovered on some of these boats in September 2016. There were approximately 600-700 workers on board these vessels, predominantly from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Kiribati. Some of these workers reported being paid less than US$1 an hour while being forced to pay off debts to their brokers and recruiters. One Indonesian worker accumulated debts of over US$5,000 to pay for getting to Hawaii, recruitment fees, and even for finding his replacement. This sum was gradually deducted from his already meagre salary. Ship owners or captains could pay up to US$10,000 to brokers for each worker, a cost which is often then transferred to the worker for the duration of their contract.

This fulfills the definition of “debt bondage” a practice recognized and banned by various treaty as a practice similar to slavery. The report uncovered similar stories off the coast of San Francisco:

Workers have also reported being verbally and physically abused. Two Indonesian men who escaped from their vessel in 2010 while it was docked in San Francisco told police how they were beaten and kicked by the vessel captain, forced to work 20-hour shifts, and denied access to medical treatment for work-related injuries. One of the victims said that food was so scarce he would often take pieces of raw fish to eat, just to keep his strength up.

So now we might be inclined to use the last refuge of cognitive dissonance: Well I eat local seafood caught in my country only, where hopefully labour laws are being respected? Once again most regrettably this is most likely not the case. For example, a Canadian investigation in 2020 by the Narwhal uncovered the following:

The people Canada relies on to ensure the West Coast trawl fishery is operating within the law are frequently subjected to threats and harassment, making it perilous for them to do their jobs.

Workplace abuse has led observers to under-report the adverse impacts of trawl fishing and resulted in an estimated 140 million pounds of wasted fish.

If that was not enough, a 2018 report by Oceana found that 44% of fish sold in Canada is mislabeled, replaced by cheaper imported species which are often the result of human animal exploitation. They state:

Beyond economic concerns, seafood fraud creates food safety and health risks, threatens our oceans, cheats honest fishers and vendors, and creates a market for illegally caught fish, which masks global human rights abuses.

There is no reason to believe these practices are unique to Canada. In what is starting to sound like a broken record from the animal agriculture industry and our previous coverage of the exploitation of human animals, the authors of many of those reports put much effort trying to identify issues and come up with various solutions. To their credit, they seem to have put a great amount of work into coming up with theoretically possible solutions. If there were a prize for the most elaborate way to keep a sinking ship afloat without actually fixing the hole in the hull from which the water is gushing in, they would surely win an award. Incredibly, they miss the most obvious solution: The killing and consumption of sea animals is not a requirement to sustain human life.

We may not care about the killing, torture and exploitation of non-human animals in the seafood industry, but it is incumbent upon us to not contribute to the torture, exploitation and killing of human animals like Supriyanto.

Our exploitation of animals is the hole, help us plug it.

Infographics

A change of lifestyle offers individuals a powerful means to combat a range of issues, including personal health problems, climate change, loss of biodiversity, global acidification, eutrophication, freshwater shortages, pandemic prevention, antibiotic resistance, save countless lives and much more. We know of no other efficient way for individuals to address these critical challenges simultaneously without waiting for government, corporate, or technological interventions. By changing lifestyle, people can take immediate and impactful action. We encourage you to embrace this lifestyle change today. Contact us for support and to connect with local communities in your area.